Frostbite is common welfare issue for backyard chickens living in areas which experience below-freezing temperatures. It is a misconception among poultry owners that "cold-hardy" breeds are invulnerable to frostbite. All chickens are susceptible to frostbite, no matter the breed. The parts of the chicken's body that are most vulnerable to frostbite are their extremities---the comb, wattles, toes, feet and legs. Roosters with single combs and large wattles have an increased risk of developing frostbite in those parts of their bodies.

Chickens and other bird species experience something called a hunting reflex, which consists of intermittent vasodilation to help preserve tissue viability in their extremities. However, as the temperature continues to drop, this vasodilation stops. As the tissue freezes and blood flow stops, extracellular ice crystals develop. This results in cell death and increased blood viscosity, which can lead to thrombosis. Vascular inflammation and thrombosis may not be limited to the damaged extremity. Birds have an increased risk of secondary damage to their heart.

Stages of frostbite

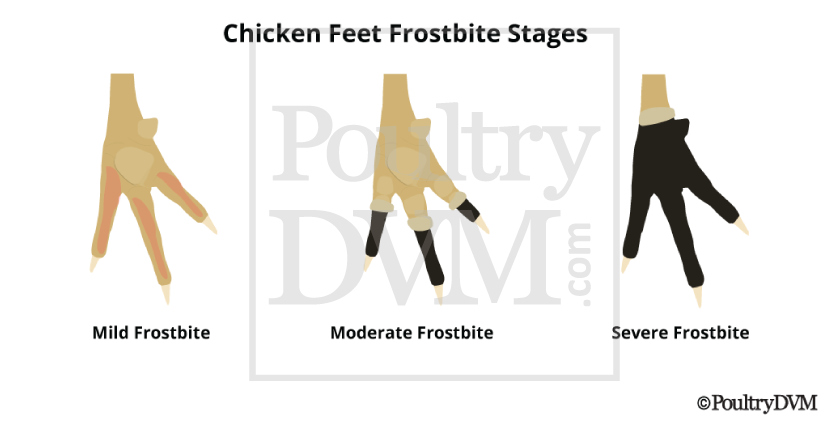

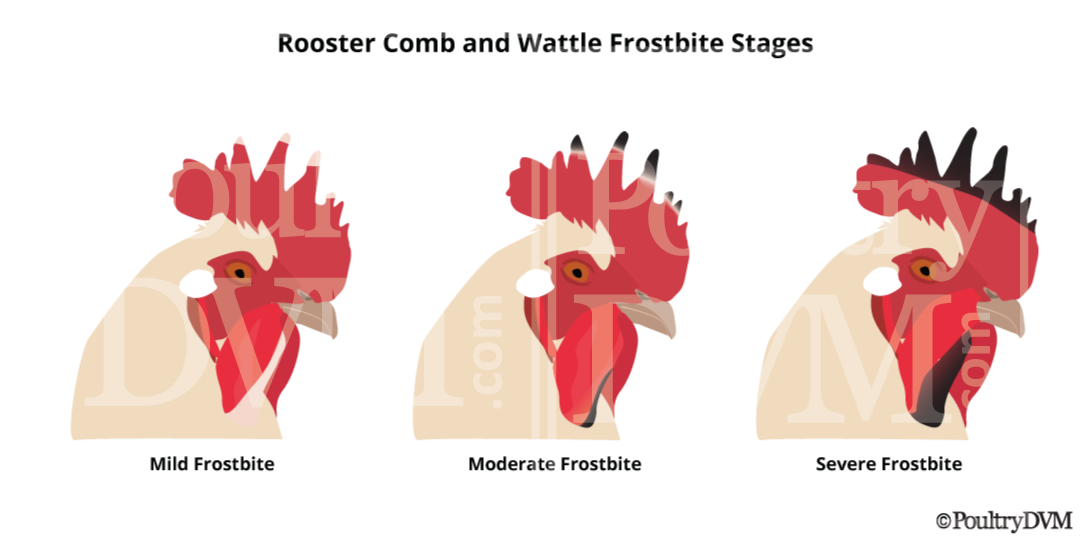

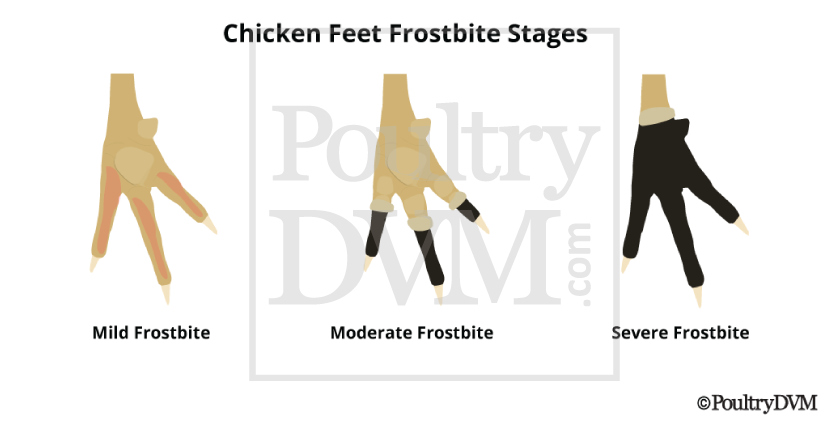

Frostbite severity can range from complete resolution without significant secondary complications, to gangrene, sloughing, and amputation of extremities following frostbite. The severity depends on factors such as absolute temperature, wind chill, duration of exposure, wet/dry cold, immersion, age, and overall health of the bird.

- First degree – Often referred to as frostnip, it involves the freezing of the surface level of skin. The bird's comb or wattles will turn an off-white, pale color. If their feet and legs are affected, they will appear slightly reddened.

- Second degree – If freezing continues, the skin may completely freeze and harden, but the deep tissues are not affected and remain normal.

- Third and fourth degrees - In severe frostbite, this stage affects all layers of skin and the tissues beneath. As the affected tissue dries, it will turn black (as a result of gangrene), and slowly mummify and fall away from the surrounding healthy tissue---at what is known as the line of demarcation. The line of demarcation in birds may take 3 to 6 weeks to develop.

When birds develop frostbite, the long-term effects seen in the surviving tissue includes increases susceptibility to cold re-injury, sensory loss, decreased circulation, and osteoarthritis.

Initial Treatment

If the tissue is still frozen, slowly warm the affected area(s) of the body. Keep the bird inside in a comfortable recovery area which will not run the risk of re-exposing them to the cold. Keep the affected body part clean and dry. Apply ointment and provide supportive care until you can bring the bird in to see a veterinarian.

It will usually take 10 days to 6 weeks for the tissue to present itself as necrotic and the line of demarcation to form. The line of demarcation is the separation between healthy tissue and dying (necrotic) tissue. This process is extremely painful for the bird. They should be taken to see a veterinarian.

What NOT to Do

- Do not use direct heat (such as a heat lamp, hair dryer, heating pads, etc,) to rewarm the affected area.

- Do not rub, massage, shake, or otherwise apply any physical force to frostbitten tissues, as it can cause more damage to the affected area.

- Do not let chickens walk on frostbitten feet or toes, as walking will increase the damage. Restrict movement through the use of a sling-type restraint.

- Do not try to remove the blackened areas. These areas actually protect the remaining, living tissue. Removing the blackened areas can expose the living tissue underneath and increase the risk of secondary infection.

- Do not put the chicken back outside.

- If there is potential for refreezing of an area, do not attempt to thaw, as thawing followed by refreezing can cause even more damage to the area.